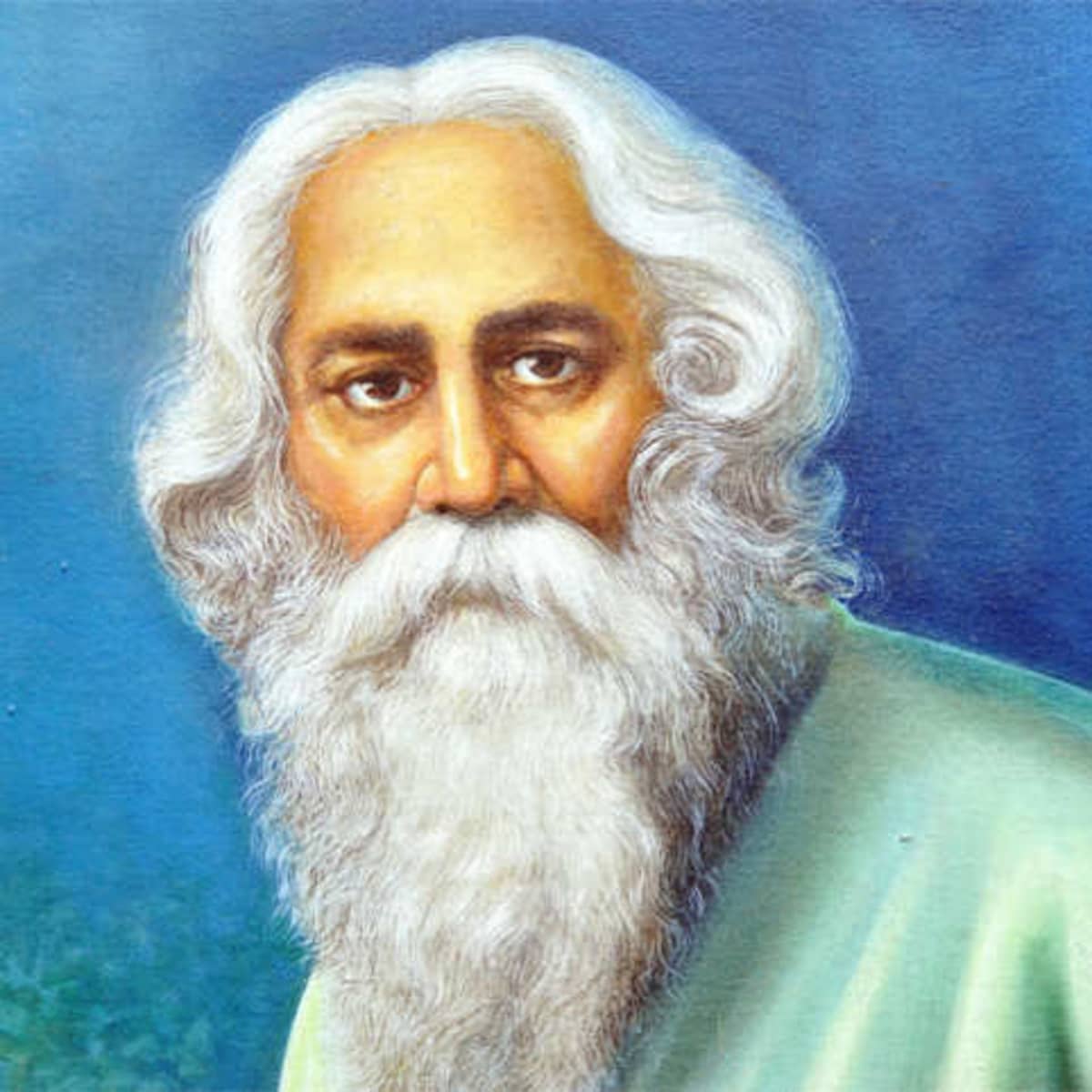

Rabindra Sangeet also known as Tagore Songs, are songs from the Indian subcontinent written and composed by the Bengali Polymath Rabindranath Tagore, winner of the 1913 Nobel Prize in Literature, the first Indian and also the first non-European to receive such recognition.

Tagore was a prolific composer with approximately 2,232 songs to his credit. The songs have distinctive characteristics in the music of Bengal, popular in India and Bangladesh.

It is characterised by its distinctive rendition while singing which includes a significant amount of ornamentation like meend, murki, etc. and is filled with expressions of romanticism.

The music is mostly based on Hindustani classical music, Carnatic Classical Music, Western tunes and the inherent folk music of Bengal and inherently possess within them, a perfect balance, an endearing economy of poetry and musicality.

Lyrics and music both hold almost equal importance in Rabindra Sangeet.

Tagore created some six new Taals (Which were actually inspired by Carnatic Talas) because he felt the traditional taals existing at the time could not do justice and were coming in the way of the seamless narrative of the lyrics.

The Rabindrasangeet contains various sections or ‘parjay’ such as ‘prem’, ‘prakriti’,’bhanusingher podaboli’, etc.

The Bhanushingher Podaboli songs are based on his own life experiences and happenstance.

History

Rabindra Sangeet merges fluidly into Tagore’s literature, most of which – poems or parts of novels, stories, or plays alike – were lyricised.

Influenced by the Thumri style of Hindustani music, they ran the entire gamut of human emotion, ranging from his early dirge-like Brahmo devotional hymns to quasi-erotic compositions.

They emulated the tonal color of classical Ragas to varying extents. Some songs mimicked a given raga’s melody and rhythm faithfully; others newly blended elements of different ragas.

Yet about nine-tenths of his work was not Bhanga Gaan, the body of tunes revamped with “fresh value” from select Western, Hindustani, Bengali folk and other regional flavours “external” to Tagore’s own ancestral culture.

In fact, Tagore drew influence from sources as diverse as traditional Hindusthani Thumri (“O Miya Bejanewale”) to Scottish ballads (“Purano Shei Diner Kotha” from “Auld Lang Syne“).

Scholars have attempted to gauge the emotive force and range of Hindustani Ragas:

the pathos of the Purabi raga reminded Tagore of the evening tears of a lonely widow, while Kanara was the confused realization of a nocturnal wanderer who had lost his way.

In Bhupali he seemed to hear a voice in the wind saying, ‘stop and come hither’. Paraj conveyed to him the deep slumber that overtook one at night’s end.

Tagore influenced Sitar maestro Vilayat Khan and Sarodiyas Buddhadev Dasgupta and Amjad Ali Khan.

His songs are widely popular and undergird the Bengali ethos to an extent perhaps rivalling Shakespeare’s impact on the English-speaking world.

It is said that his songs are the outcome of five centuries of Bengali literary churning and communal yearning.

These songs transcend the mundane to the aesthetic and express all ranges and categories of human emotions.

The poet gave voice to all – big or small, rich or poor. The poor Ganges boatman and the rich landlord air their emotions in them.

They birthed a distinctive school of music whose practitioners can be fiercely traditional: novel interpretations have drawn severe censure in both West Bengal and Bangladesh.

For Bengalis, the songs’ appeal, stemming from the combination of emotive strength and beauty described as surpassing even Tagore’s poetry, was such that the Modern Review observed that there is in Bengal no cultured home where Rabindranath’s songs are not sung or at least attempted to be sung.

Even illiterate villagers sing his songs.

In 1971, Amar Shonar Bangla became the national anthem of Bangladesh. It was written ironically to protest the 1905 Partition of Bengal along communal lines: lopping Muslim-majority East Bengal from Hindu-dominated West Bengal was to avert a regional bloodbath.

Tagore saw the partition as a ploy to upend the independence movement, and he aimed to rekindle Bengali unity and tar communalism. Jana Gana Mana was written in Shadhu-Bhasha, a Sanskritised register of Bengali, and is the first of five stanzas of a Brahmo hymn that Tagore composed.

It was first sung in 1911 at a Calcutta session of the Indian National Congress and was adopted in 1950 by the Constituent Assembly of the Republic of India as its national anthem.

Songs

His songs are affectionately called Rabindra Sangeet, and cover topics from humanism, structuralism, introspection, psychology, romance, yearning, nostalgia, reflection, modernism.

Rabindra Sangeet offers a melody for every season of Bengal, and for every aspect of Bengali life.

Tagore primarily worked with two subjects – first, the human being, the being and the becoming of that human being, and second, Nature, in all her myriad forms and colours, and of the relationship between the human being and Nature and how Nature affects the behavior and the expressions of human beings.

Bhanusimha Thakurer Padavali (or Bhanusingher Podaboli), one of Tagore’s earliest works in music, was primarily in a language that is similar and yet different from Bengali.

This language, Brajabuli, was derived from the language of the Vaishnav hymns, and of texts like Jayadeva‘s Gita Govinda, some influences from Sanskrit can be found, courtesy Tagore’s extensive homeschooling in the Puranas, the Upanishads, as well as in poetic texts like Kalidasa‘s Meghadūta and Abhigyanam Shakuntalam.

Tagore was one of the greatest narrators of all time, and throughout his life, we find a current of narration through all his works that surges with upheavals in the psyche of the people around him, as well as with the changes of seasons.

A master of metaphor, it is often difficult to identify the true meaning that underlies his texts, but what is truly great about Tagore, is that his songs are identifiable with any and every possible mood, with every possible situation that is encountered by a person in the course of life.

This truly reinforces the notion that Rabindrasangeet has at its heart some unbelievably powerful poetry.

The Upanishads influenced his writing throughout his life, and his devotional music is addressed almost always to an inanimate entity, a personal, a private god, whom modernists call the Other.

Rabindranath Tagore was a curator of melodic and compositional styles. In the course of his travels all over the world, he came into contact with the musical narratives of the West, of the South of India, and these styles are reflected in some of his songs.

There are several classifications of his work. The ones that beginners most often use is that based on genre – devotional (Puja Porjaay), romantic (Prem Porjaay)

[Note: It often becomes difficult, if not impossible, on hearing a song, to determine if it falls in the devotional genre or the romantic.

The line between the two is blurred, by certain creations of Tagore himself, e.g. Tomarei Koriyachi Jibonero Dhrubotara. Also, Tagore never made these divisions.

Only after his death was the need felt to categorize, compile and thus preserve his work, and the genre-classification system was born out of this need.] seasonal (Prokriti Porjaay) – summer (Grishho), monsoon (Borsha), autumn (Shorot), early winter (Hemonto), winter (Sheet), Spring (Boshonto); diverse (Bichitro), patriotic (Deshatmobodhok).

Although Deshatmobodh and patriotism are completely antipodal concepts, yet the difficulties of translation present themselves, apart from songs specified for certain events or occasions (Aanushtthanik) and the songs he composed for his numerous plays and dance-dramas.

Sangee

The book forming a collection of all 2,233 songs written by Rabindranath is called Gitabitan (“Garden of songs”) and forms an important part of extant historical materials pertaining to Bengali musical expression.

The six major parts of this book are Puja (worship), Prem (love), Prakriti (seasons), Swadesh (patriotism), Aanushthanik (occasion-specific), Bichitro (miscellaneous) and Nrityonatya (dance dramas and lyrical plays).

The Swarabitan, published in 64 volumes, includes the texts of 1,721 songs and their musical notation. The volumes were first published between 1936 and 1955.

Earlier collections, all arranged chronologically, include Rabi Chhaya (1885), Ganer Bahi o Valmiki Pratibha (1893), Gan (1908), and Dharmashongit (1909).

Exponents

Since the establishment of the Sangeet Bhavan of Tagore’s own Visva-Bharati University at Shantiniketan, along with its codification of Rabindra Sangeet instruction, multiple generations have created Rabindra Sangeet (its aesthetics and singing style) into a tangible cultural tradition breeding many singers who now specialize in singing Tagore’s works.

Some notable early exponents of Rabindra Sangeet who laid down its foundations and continue to inspire generations of singers include: Kanika Banerjee. Suchitra Mitra, Hemant Kumar, Debabrata Biswas, Sagar Sen, Subinoy Roy, and Chinmoy Chattopadhyay.

Historical influence

Rabindra Sangeet has been an integral part of Bengal culture for over a century.

Hindu monk and Indian social reformer Swami Vivekananda became an admirer of Rabindra Sangeet in his youth. He composed music in the Rabindra Sangeet style, for example Gaganer Thale in Raga Jaijaivanti.

Many of Tagore’s songs form the worship hymnal and hymns in many Churches in Kolkata and West Bengal. Some examples are Aaguner Poroshmoni, Klanti Amar Khoma Koro Probhu, Bipode More Rokkha Koro and Aanondoloke Mongolaloke.

One reply on “Melodies of Rabindra Sangeet: The Musical Creations of Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore”

Fantastic coverage

Great thoughts and observations