ॐ श्री गुरुभ्यो नमः ॐ श्री शिवानन्दाय नमः ॐ श्री चिदानन्दाय नमः ॐ श्री दुर्गायै नमः

Source of all Images in this Blog-post : Google Images : ‘Google Image Search’ will reveal the multiple sources of every single image shared in this Blog. For more details, kindly see ‘Disclaimer‘

Delhi Crafts Council’s Covid-19 Atisans Help Fund

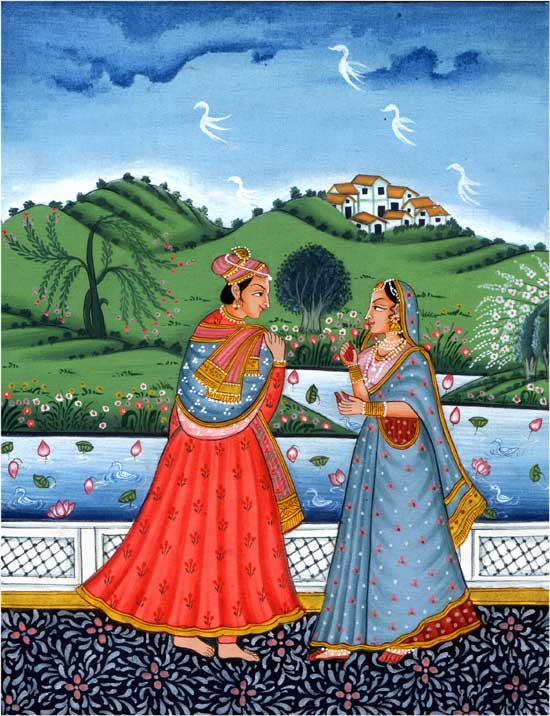

Pahari denotes ‘hilly or mountainous’ in origin. Pahari Schools of Painting includes towns, such as Basohli, Guler, Kangra, Kullu, Chamba, Mankot, Nurpur, Mandi, Bilaspur, Jammu and others in the hills of western

Himalayas, which emerged as centres of painting from seventeenth to nineteenth century.

Beginning at Basohli with a coarsely flamboyant style, it blossomed into the most exquisite and sophisticated style of Indian painting known as the Kangra School, through the Guler or pre-Kangra phase.

Unlike the distinguishing stylistic features of Mughal, Deccani and Rajasthani Schools, Pahari paintings demonstrate challenges in their territorial classification.

Though all the above centres crafted precisely individualistic characteristics in painting (through the depiction of nature, architecture, figural types, facial features, costumes, preference for particular colours and such other

things), they do not develop as independent schools with distinctive styles.

Paucity of dated material, colophons and inscriptions also prevent informed categorisation.

The emergence of the Pahari School remains unclear, though scholars have

cautiously proposed theories concerning its beginning and influences.

It is widely accepted that Mughal and Rajasthani styles of paintings

were known in the hills probably through examples of Provincial Mughal style and family relationships of hill Rajas with the royal courts of Rajasthan.

However, the flamboyantly bold Basohli-like style is, generally, understood to

be the earliest prevailing pictorial language.

This argument is also true for Rajasthani schools as attribution merely by regions creates vagueness and several disparities remain unexplained. Hence, if a family of artists is considered as the style bearer, justification of multiple strands of a style can be accommodated within the same region and school.

Scholars agree that in the early eighteenth century, the style of the Seu family and others conformed to the Basohli idiom.

However, from middle of the eighteenth century, the style transformed through a pre-Kangra phase, maturing into the Kangra style.

This abrupt transformation in style and beginning of experimentation, which gave rise to varied stylistic idioms related to different Pahari centres, is largely ascribed to responses by various artist families and paintings (especially, the Mughal style) that were introduced in the Pahari kingdoms.

This sudden arrival of paintings, which might have been introduced through rulers, artists, traders or any such agency or event, impacted local artists and profoundly influenced their painting language.

Most scholars, now, dispute the earlier hypothesis that the sudden change was caused and initiated by the migration of artists from the Mughal atelier.

For Goswamy, it was the naturalism in these paintings that appealed to the sensibilities of Pahari artists.

Compositions, worked out from a relative point of view, show some paintings with decorated margins. Themes that included recording the daily routine or important occasions from the lives of kings, creation of new prototype for female form and an idealised face, are all associated with this newly

emerging style that gradually matures to the Kangra phase.

Basohli School

The first and most dramatic example of work from the hill states is from Basohli. From 1678 to 1695, Kirpal Pal, an enlightened prince, ruled the state. Under him, Basohli developed a distinctive and magnificent style.

It is characterised by a strong use of primary colours and warm yellows filling the background and horizon, stylised treatment of vegetation and raised white paint for imitating the representation of pearls in ornaments.

However, the most significant characteristic of Basohli painting is the use of small, shiny green particles of beetle wings to delineate jewellery and simulate the effect of emeralds.

In their vibrant palette and elegance, they share the aesthetics of the Chaurpanchashika group of paintings of Western India.

The most popular theme of Basohli painters was the Rasamanjari of Bhanu Datta. In 1694–95, Devida, a tarkhan (carpenter–painter), did a magnificent series for his patron Kirpal Pal.

Bhagvata Purana and Ragamala were other popular themes. Artists also painted portraits of local kings

with their consorts, courtiers, astrologers, mendicants, courtesans and others.

While artist ateliers from Basohli, gradually, spread to other hill states, such as Chamba and Kullu, giving rise to local variations of the Basohli kalam.

A new style of painting came in vogue during 1690s to 1730s, which was referred to as the Guler–Kangra phase.

Artists during this period indulged in experimentation and improvisations that finally resulted and moulded into the Kangra style.

Hence, originating in Basohli, the style gradually spread to other hill states of Mankot, Nurpur, Kullu, Mandi, Bilaspur, Chamba, Guler and Kangra.

The Sanskrit epic, Ramayana, was one of the favourite texts of the hill artists at Basohli, as well as, Kullu. This set derives its name from ‘Shangri’, the place of residence of a branch of the Kullu royal family, patrons and formerly possessors of this set. These works of Kullu artists were influenced in varying degrees by the styles of Basohli and Bilaspur.

Rama learns of his exile and prepares to leave Ayodhya along with his wife Sita and brother Lakshmana. Maintaining equanimity of mind, Rama indulges in his last acts of giving away his possessions.

At the request of Rama, his brother piles up his belongings and the crowd begins to gather to receive the largesse of their beloved Rama—jewellery,

sacrificial vessels, thousand cows and other treasures.

Guler School

The first quarter of the eighteenth century saw a complete

transformation in the Basohli style, initiating the

Guler–Kangra phase.

This phase first appeared in Guler, a

high-ranking branch of the Kangra royal family, under the

patronage of Raja Govardhan Chand (1744–1773).

Guler

artist Pandit Seu with his sons Manak and Nainsukh are

attributed with changing the course of painting around

1730–40 to a new style, usually, referred to as the pre–Kangra

or Guler–Kangra kalam.

This style is more refined, subdued

and elegant compared to the bold vitality of the Basohli style.

Though initiated by Manak, also called Manaku, his brother

Nainsukh, who became the court painter of Raja Balwant

Singh of Jasrota, is responsible for shaping the Guler School

emphatically.

The most matured version of this style entered

Kangra during the 1780s, thus, developing into the Kangra

School while the offshoots of Basohli continued in Chamba

and Kullu, India.

Sons and grandsons of Manak and Nainsukh worked

at many other centres and are responsible for the finest

examples of Pahari paintings.

Guler appears to have a long tradition of paintings

amongst all Pahari schools. There is evidence that artists

were working in Haripur–Guler ever since the reign of Dalip

Singh (1695–1743) as many of his and his son Bishan Singh’s

portraits, dating back to earlier than 1730s, i.e., before the

beginning of the Guler–Kangra phase can be found.

Bishan Singh died during the lifetime of his father Dalip Singh. So, his younger brother Govardhan Chand ascended to the throne that witnessed a change in painting style.

Manak’s most outstanding work is a set of Gita Govinda

painted in 1730 at Guler, retaining some of the elements of

the Basohli style, most strikingly the lavish use of beetle’s

wing casings.

Nainsukh appears to have left his hometown in Guler and

moved to Jasrota. He is believed to have initially worked for

Mian Zoravar Singh, whose son and successor Balwant Singh

of Jasrota was to become his greatest patron.

Nainsukh’s celebrated pictures of Balwant Singh are unique in the kind

of visual record they offer of the patron’s life. Balwant Singh

is portrayed engaged in various activities — performing puja,

surveying a building site, sitting in a camp wrapped in a quilt

because of the cold weather, and so on.

The artist gratified his patron’s obsession by painting him on every possible

occasion. Nainsukh’s genius was for individual portraiture

that became a salient feature of the later Pahari style.

His palette comprised delicate pastel shades with daring expanses of white or grey.

Manaku, too, did numerous portraits of his enthusiastic

patron Raja Govardhan Chand and his family. Prakash

Chand, successor of Govardhan Chand, shared his father’s

passion for art and had sons of Manaku and Nainsukh,

Khushala, Fattu and Gaudhu as artists in his court.

Kangra School

Painting in the Kangra region blossomed under the patronage

of a remarkable ruler, Raja Sansar Chand (1775–1823).

It

is believed that when Prakash Chand of Guler came under

grave financial crisis and could no longer maintain his atelier,

his master artist, Manaku, and his sons took service under

Sansar Chand of Kangra.

Sansar Chand ascended to the throne at the tender age

of 10 years after the kingdom had been restored to its earlier

glory by his grandfather Ghamand Chand.

They belonged to the Katoch dynasty of rulers, who had been ruling the Kangra region for a long time until Jahangir conquered their territory

in the seventeenth century and made them his vassals.

After the decline of the Mughal power, Raja Ghamand Chand

recovered most of the territory and founded his capital town

of Tira Sujanpur on the banks of river Beas and constructed

fine monuments. He also maintained an atelier of artists.

Raja Sansar Chand established supremacy of Kangra

over all surrounding hill states. Tira Sujanpur emerged as

the most prolific centre of painting under his patronage.

An earlier phase of Kangra kalam paintings is witnessed in

Alampur and the most matured paintings were painted at

Nadaun, where Sansar Chand shifted later in his life. All

these centres were on the banks of river Beas. Alampur

along with river Beas can be recognised in some paintings.

Less number of paintings was done in Kangra as it remained

under the Mughals till 1786, and later, the Sikhs.

Sansar Chand’s son Aniruddha Chand (1823–1831),

too, was a generous patron and is often seen painted with

his courtiers.

The Kangra style is by far the most poetic and lyrical

of Indian styles marked with serene beauty and delicacy

of execution. Characteristic features of the Kangra style

are delicacy of line, brilliance of colour and minuteness of

decorative details. Distinctive is the delineation of the female

face, with straight nose in line with the forehead, which came

in vogue around the 1790s is the most distinctive feature of

this style.

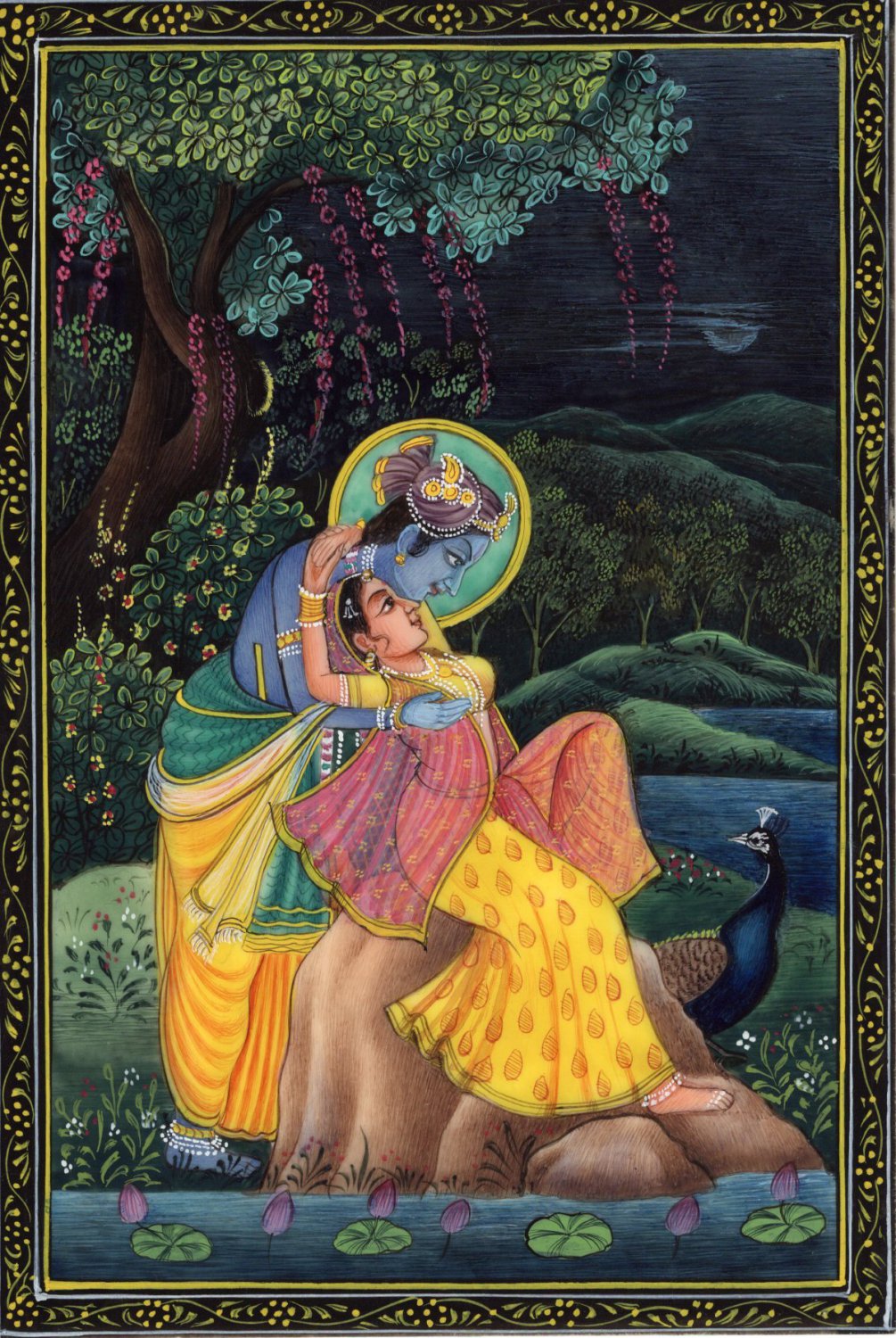

Most popular themes that were painted were the

Bhagvata Purana, Gita Govinda, Nala Damayanti, Bihari

Satsai, Ragamala and Baramasa. Many other

paintings comprise a pictorial record of Sansar

Chand and his court. He is shown sitting by

the riverside, listening to music, watching

dancers, presiding over festivals, practising

tent pegging and archery, drilling troops, and

so on and forth. Fattu, Purkhu and Khushala

are important painters of the Kangra style.

During Sansar Chand’s reign, the

production of Kangra School was far greater

than any other hill state. He exercised wide

political power and was able to support a

large studio with artists from Guler and other

areas. The Kangra style soon spread from Tira

Sujanpur to Garhwal in the east and Kashmir in

the west. Painting activity was severely affected

around 1805 when the Gurkhas besieged the

Kangra fort and Sansar Chand had to flee to

his hill palace at Tira Sujanpur. In 1809, with

Krishna playing Holi with

gopis, Kangra, 1800, National

Museum, New Delhi, India

1_5.Pahari Painting.indd 75 01 Sep 2020 02:32:08 PM

2021–22

76 An Introduction to Indian Art—Part II

the help of Ranjit Singh, the Gurkhas were driven away.

Though Sansar Chand continued to maintain his atelier of

artists, the work no longer paralleled masterpieces of the

period 1785–1805.

This series of Bhagvata Purana paintings is one of the

greatest achievements of Kangra artists. It is remarkable for

its effortless naturalism, deft and vivid rendering of figures in

unusual poses that crisply portray dramatic scenes. The

principal master is believed to have been a descendent of

Nainsukh, commanding much of his skill.

With minds engrossed in thoughts of Krishna, the gopis

recall and enact his various lilas or feats. Some of them

being—the killing of Putana, liberation of Yamala–Arjun

after Krishna was tied to a mortar by Yashoda, lifting of

Mount Govardhan and rescuing the inhabitants of Braj from

the heavy downpour and wrath of Indra, subduing of serpent

Kaliya, and the intoxicating call and allure of Krishna’s

flute. The gopis take on different roles and emulate his

divine sports.

The Kangra School came to fore in the 1780s while the

offshoots of the Basohli style emerged and continued in

centres such as Chamba, Kullu, Nurpur, Mankot, Jasrota,

Mandi, Bilaspur, Jammu and others with some of their

specific characteristics. In Kashmir (1846–1885), the Kangra

style initiated a local school of Hindu book illumination. The

Sikhs employed other Kangra painters eventually.

There is a broad classification of three styles—Basohli,

Guler and Kangra, and scholars may have variant terms for

the same. However, these are indicative centres from where

the style travels elsewhere. Hence, in Jasrota, as one observes

the Guler style, it becomes categorised under the Guler

School with Jasrota as one of its centres. Briefly mentioning

the aspects of the other centres, one finds portraits of the

rulers of Chamba in the seventeenth and early eighteenth

century in the Basohli style.

Kullu emerged with a distinctive style, where figures

had a prominent chin and wide open eyes, and lavish use

of grey and terracotta red colours in the background was

made. Shangri Ramayana is a well-known set painted in the

Kullu Valley in the last quarter of the seventeenth century.

Paintings of this set vary from each other in style, and, thus it

is believed that these were painted by different sets of artists.

It is believed that when the Basohli style had outgrown itself

and matured into the Kangra style, Nurpur artists retained

the vibrant colours of Basohli with the dainty figure types

of Kangra.

Due to marital relations between Basohli and Mankot, few

artists from Basohli seem to have shifted to Mankot, thereby,

developing a similar school of painting. While Jasrota had

an indulgent patron in Balwant Singh and the school is

well-known through his numerous portraits painted by his

court artist, Nainsukh, who led the earlier simple Basohli

style to new sophistication. This style of Nainsukh is also

referred to as the Guler–Kangra style.

Rulers of Mandi were ardent worshippers of Vishnu and

Shiva. Hence, apart from the Krishna Lila themes, Shaivite

subjects were also painted. An artist named Molaram is

associated with the Garhwal School. Several signed paintings

by him have been discovered. This school was influenced by

the Kangra style of Sansar Chand phase.

Delhi Crafts Council’s Covid-19 Atisans Help Fund